Fertility rates are falling in Australia, here's why the government is concerned.

If you’re in the stage of life where some friends are entering their #parentingera you may have also noticed a growing trend of couples choosing not to have children.

A survey by KPMG revealed that many young Australians, even those that want to have children, are changing their plans or opting out of parenthood due to rising cost of living.

When Aussies are already feeling the strain of everyday life without kids, it’s hard to imagine bringing a baby (and related costs) into the picture.

But Australia’s low fertility is reaching a critical tipping point and the government is crashing out.

Why does the government care about people not having babies?

You see, when the fertility rate is too low there’s a massive domino effect on the economy.

Since Australia’s healthcare system and government services rely heavily on funding from individual income taxes, it’s important to have young people entering the workforce (aka paying taxes!).

But with the current downwards fertility trend, Australia has an ageing population problem. That means Australia runs the risk of having too many people relying on social welfare (through pensions and medicare benefits, etc.) without enough people funding it (through income taxes).

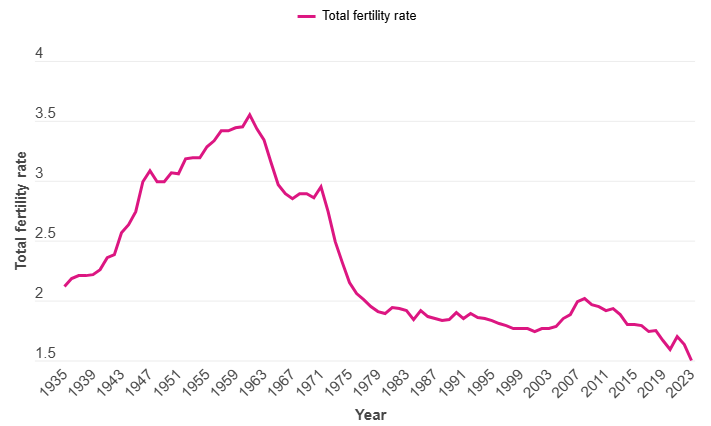

Let’s get down to the nitty gritty numbers. Economists have calculated a “replacement rate” of 2.1 babies per woman needed to sustain Australia’s current standard of living. But here’s the thing: Australia’s 2024 total fertility rate was only 1.51… and has actually been below the recommended replacement rate since 1976.

Australia’s total fertility rate from 1935 to 2023

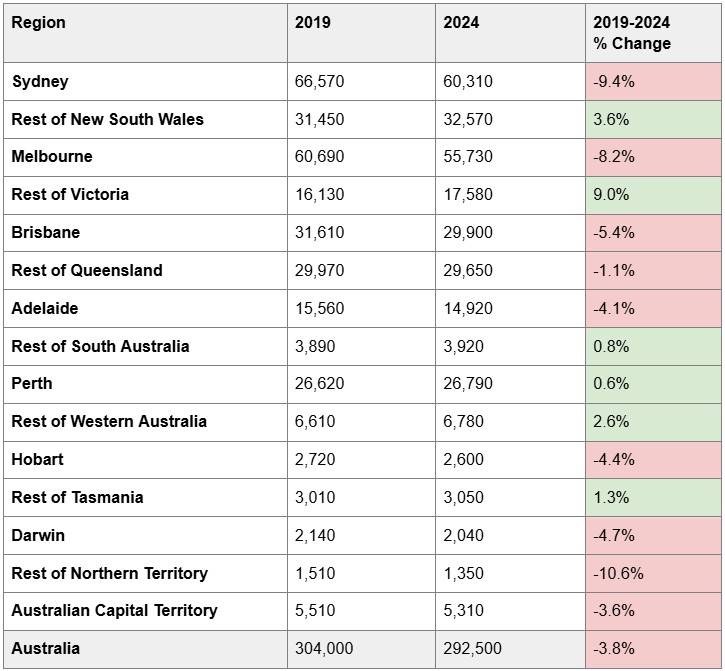

This issue is especially obvious in major cities where the cost of rent, mortgages, and childcare have grown substantially post-covid.

Number of births in Australian states across 2019-2024

We’re not alone in this baby recession.

A 2024 report by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) revealed the fertility rate dropped from an average of 3.3 (1960) to 1.5 (2022) across all 38 OECD countries, with the lowest being 0.7 children per woman in South Korea (2023).

This report also highlighted that young people aren’t just worried about the economic challenges of being a parent, but also have climate change and gender inequality at the forefront of their decision making process.

In 2004, Prime Minister John Howard introduced a ‘baby bonus’ of $3,000 to encourage more women to have children, however, some have argued this one-off incentive is not enough in today’s cost of living crisis.

Australia’s current government is proposing more long term policy changes to support new parents - like guaranteed three days of subsidised childcare, increasing paid parental leave, and paying super on government funded parental leave to reduce the gender super gap.

However, these changes are still in discussion… So for now, the baby case remains unresolved.

Disclaimer: All information contained in the Flux app, www.flux.finance, www.joinflux.com, app.flux.finance and any podcast of Flux Media Pty Ltd (ABN 27 639 804 345) is for education and entertainment purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional financial, legal or tax advice. While we do our best to provide accurate information on the podcast, we accept no responsibility for any inaccuracies that may be communicated.

Flux does not operate under an Australian financial services licence and relies on the exemption available under section 911A(2)(eb) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and ASIC RG 36.66. Flux Technologies Pty Ltd provides general advice on credit products under our own Australian Credit Licence No. 530103.

Sign up for Flux and join 100,000 members of the Flux family