Australia’s inflation and unemployment aren’t behaving like the classic Phillips curve, leaving the RBA juggling rate cuts with rising price pressures.

When economists pull out their stethoscopes - I mean… spreadsheets - to do a health check on the economy, they look at a number of factors. But the two biggest indicators are inflation and the unemployment rate.

Inflation and unemployment aren’t exactly related but they do tend to have an inverse relationship…most of the time.

So what does that mean? Well, when inflation is decreasing (like at the start of the year), unemployment tends to increase (yikes).

But when inflation is high (like post-covid times), unemployment tends to be low (silver lining?)

But the relationship between them is a little more complicated than that, so let’s piece it together.

Inflation reduces your purchasing power - meaning that when we experience inflation, the same amount of money buys you less stuff.

When inflation is high, those Red Rock Deli chips jump from $4 to $6. It huuuuurts. And it’s not sustainable. If we don’t put a stop to this, those delicious chippies will be $12 before we know it.

So the RBA raises the cash rate so that life becomes more expensive for individuals and businesses - ultimately leading people to spend less so that inflation calms TF down. That’s what happened between May 2022 and November 2023 when the RBA increased the cash rate 13 times.

The unemployment rate measures the percentage of people in the labour force who are ready and willing to work… but don’t have a job.

Economists look at this figure to get an idea of how strong and healthy the economy is; kinda like checking the economy’s blood pressure.

So, when the economy is strong, glowy and living its best life, unemployment is low, and major growth is happening.

But because of the tight labour market, employers have to compete for workers, which can drive up wages. And this growth in wages increases business costs. To protect their margins, businesses will often lift their prices. And that explains why your sub-standard co-worker is being paid more than you.

There’s a second part too. When more people are employed and earning well, they tend to spend more. More spending means higher demand for goods and services. If demand grows faster than supply can keep up, prices rise. That’s the demand driven side of inflation

Whereas if unemployment is high, this can have a cooling effect on prices, potentially reducing inflation.

Well…maybe?

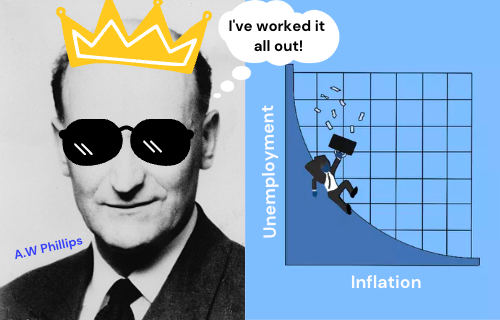

A famous economist, A.W Phillips came up with the theory that there’s an inverse or opposite relationship between unemployment and inflation, and his theory is called the Phillips curve.

You’ve gotta name your economic theory after yourself, right?

Now, his theory poses a sticky situation for economists and policymakers because it basically implies that as the RBA increases the cash rate, it is likely going to put people out of jobs.

But economists aren’t so sure that the Phillips curve is always accurate, especially in the developed world.

In the years leading up to the pandemic, inflation was low and unemployment and wage growth was the slowest it’s ever been.

And after the pandemic, we saw the job rate remain pretty solid and prices absolutely shoot for the sky.

Soooo instead of moving in the opposite direction, inflation and unemployment were both easing.

This year, the RBA has been cautiously cutting the cash rate to ease Australia’s high cost of living… all while balancing the risk of inflation flaring up again and unemployment rates creeping up.

And while things were looking pretty good earlier this year (quarterly inflation came down to 2.8% in July, within the RBA’s 2-3% target range) recent data shows CPI is not behaving as the RBA would like.

October’s monthly inflation hit 3.8% which means consumer spending is rebounding faster and harder than expected.

And what about unemployment rates you ask?

Despite what the theory suggests, unemployment rates have remained relatively stable around 4-4.5% with a slight slowing down in job growth - but no alarming changes (yet).

Sooo yeah… if inflation and unemployment rates aren’t following the old Phillips rulebook anymore, perhaps the RBA’s got some improvising to do!

Disclaimer: All information contained in the Flux app, www.flux.finance, www.joinflux.com, app.flux.finance and any podcast of Flux Media Pty Ltd (ABN 27 639 804 345) is for education and entertainment purposes only. It is not intended as a substitute for professional financial, legal or tax advice. While we do our best to provide accurate information on the podcast, we accept no responsibility for any inaccuracies that may be communicated.

Flux does not operate under an Australian financial services licence and relies on the exemption available under section 911A(2)(eb) of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) and ASIC RG 36.66. Flux Technologies Pty Ltd provides general advice on credit products under our own Australian Credit Licence No. 530103.

Sign up for Flux and join 100,000 members of the Flux family